STARS MEET STARSEMINENT GUESTS FOR THE ANNIVERSARY

The Städel is celebrating its 200th birthday.

THE VISITORS BECOMETHEIR OWN OBSERVERS

Thomas Struth’s museum photographs

Two famous paintings by Jacques-Louis David can be seen in the photograph. David is considered a chief exponent of Neoclassicist painting in the France of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The painting at the centre shows the coronation of Napoleon. To its right, a scene from the story of the Rape of the Sabines is depicted.

On closer inspection, the seemingly coincidental arrangement of the museum visitors in the room looks precisely calculated, as if the people in the museum were making direct reference to the figures in the paintings with their positions and poses. One group of visitors stands reverently in front of the depiction of Napoleon’s coronation, thus mirroring the demeanour of the figures in the painting, who look on solemnly as the ceremony takes its course.

The visitors in front of the Intervention of the Sabine Women, on the other hand, are seated in haphazard fashion – as if to imitate the figural arrangement of the turbulent scene in the painting. The German artist Thomas Struth (b. 1954) employs the photography medium to forge a link between painted and real space. Once competing media, painting and photography now enter into a dialogue that reformulates the question as to reality’s representation.

Thomas Struth photographed the scene at the Musée du Louvre in Paris in 1989. He took further shots for his Museum Photographs series at the National Gallery in London, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Art Institute of Chicago.

For Struth, the museum institution is not only a place for looking at art, but also one where art is created. The Museum Photographs series mirrors his interest in urban life, architecture and human civilization. In the contemplation of Struth’s works, the viewer is inevitably called upon to become aware of – and critically question – his own attitude towards art.

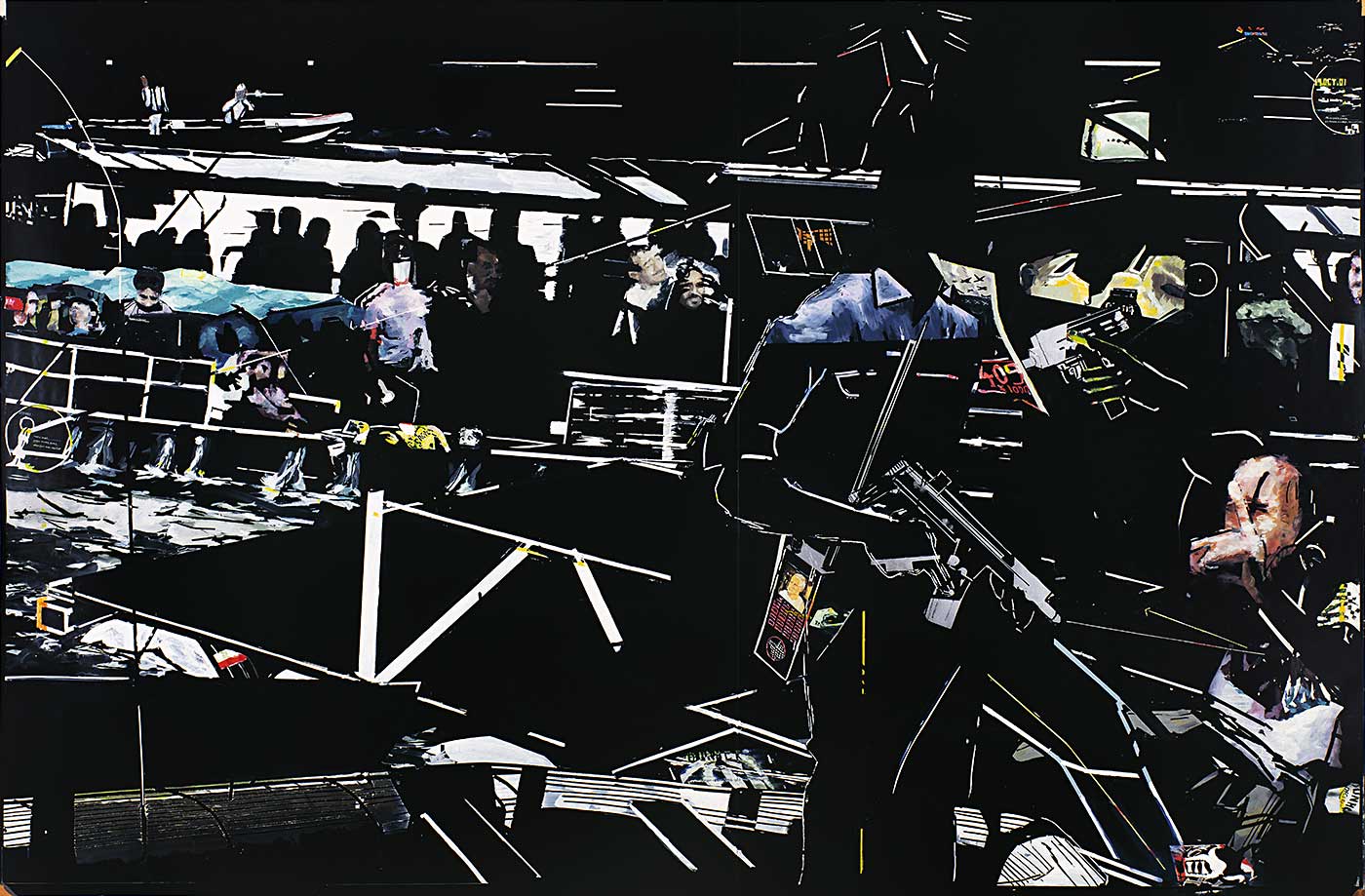

APELLES ANDTHE SCHOLAR

Quentin Massys meets Willem van Haecht

Up to the very ceiling of the high room, artworks of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries hang closely side by side and one above the other. In the midst of this striking scene sits Apelles, the most prominent painter of antiquity, before his easel. He scrutinizes his model Campaspe, the concubine of Alexander the Great. Full of admiration, the commander looks over the artist’s shoulder, watching him at work.

As the legend has it, Apelles falls deeply in love with the beautiful woman while painting her. Alexander notices his painter’s burning passion and gives him Campaspe as a gift. He keeps the painting, however: in his eyes, she is even more beautiful in the portrayal than in real life. By depicting this legend, van Haecht was alluding to the primacy of art over nature.

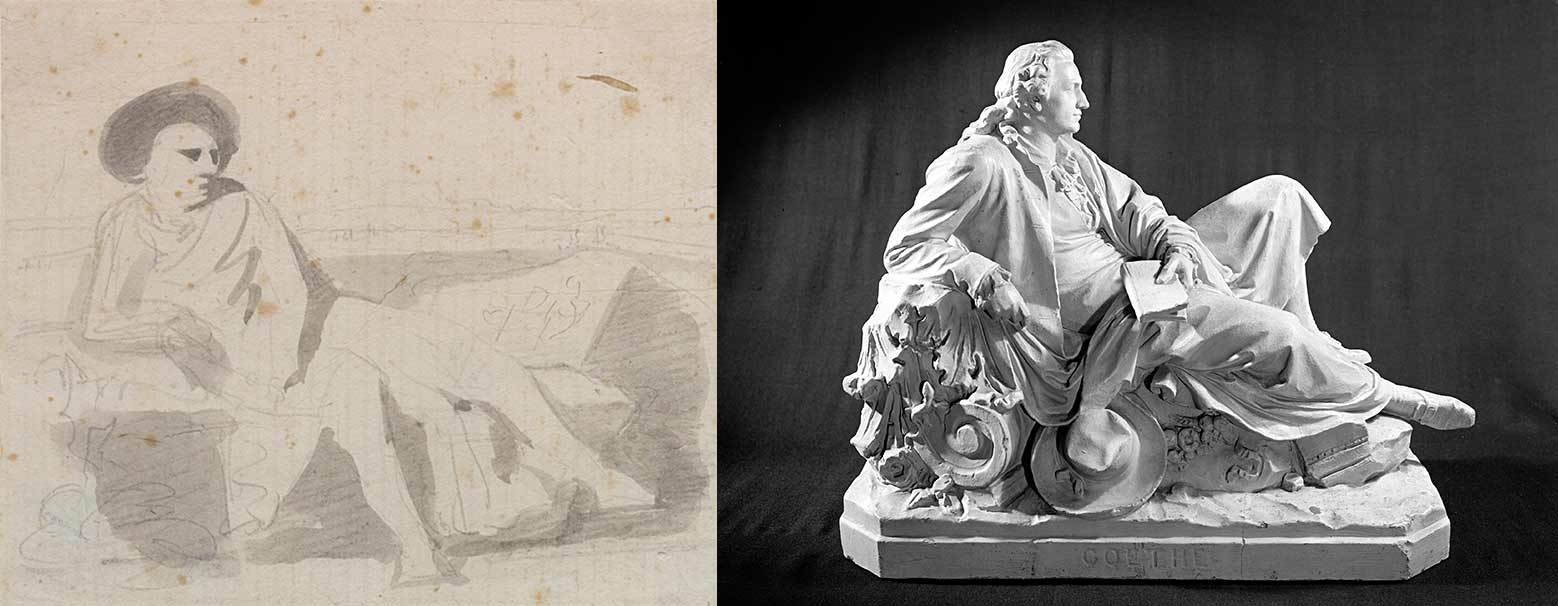

THE PAINTER ANDTHE POET

Tischbein in Italy

During his travels in Italy in 1786, Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749–1832) shared quarters in Rome with Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein and other artists. When Tischbein was compelled to turn his back on Italy several years later, he left the portrait of Goethe behind – still in an unfinished state – in Naples, his last place of residence. It remained undated and unsigned.

It is possible that the painting was completed at a later date by a different, and less practised, hand. It could explain the mysterious second left foot.

The work entered the Städel Museum collection in 1887 as a gift from Adèle von Rothschild, and quickly became a crowd puller. It undoubtedly owes its success less to its painterly quality than to the cult surrounding Goethe, the “prince of poets”.

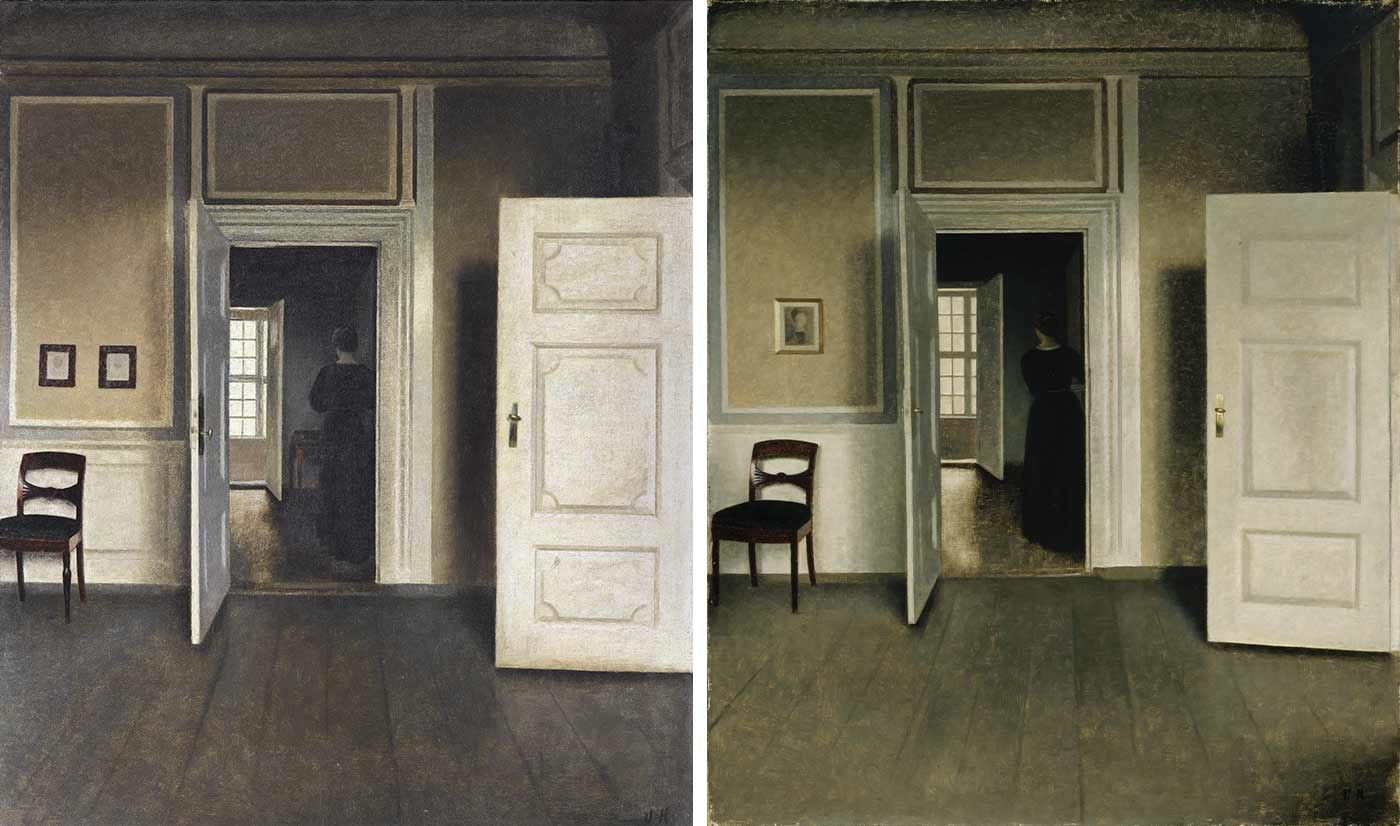

OPENDOORS

Hammershøi’s interiors

Between 1898 and 1909, Hammershøi executed some eighty depictions of interiors. In the process, he took orientation from his own flat in Copenhagen. The brick building in Strandgade 30 dates from the seventeenth century and still exists today. The painter lived here with his wife Ida, who often posed for him. The unusually sparse furnishings of their flat contrasted strongly with the prevailing interior decoration tastes of the time.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, interiors became ever more important: in the age of industrialization, the cities grew rapidly, and a person’s home was often his only retreat from the fast-paced hustle and bustle of urban life. Those who had the financial means at their disposal furnished their residences with sumptuously embellished curtains, valuable carpets and ornate furniture. In Hammershøi’s paintings, however, there is nothing to create an impression of a safe and cosy home.

INTERIORS WITH IDA

Her back faces the viewer; her dark dress is plain and inconspicuous. All the doors around her are open. If we extend the lines of the doors’ edges into space, however, Ida is virtually encircled. Disconcerting, tension-filled elements of this kind are characteristic of Hammershøi’s works.

He painted a further version of the Frankfurt work in 1905: this particular depiction seems to have been important to him. Comparison reveals subtle differences: where there were originally two pictures on the dining room wall, now there is only one. The little side table next to Ida is missing. The interior of the second version appears deeper.

It is as if Hammershøi was reducing the depiction object by object until he ultimately advanced to its core.

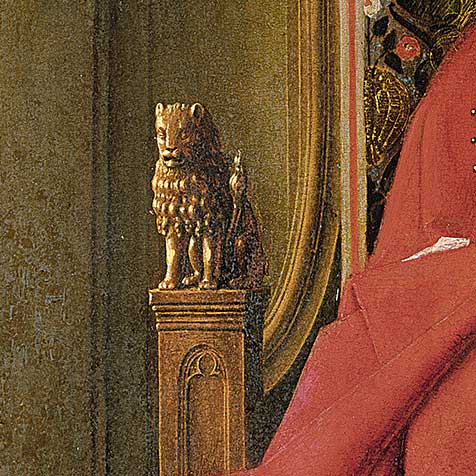

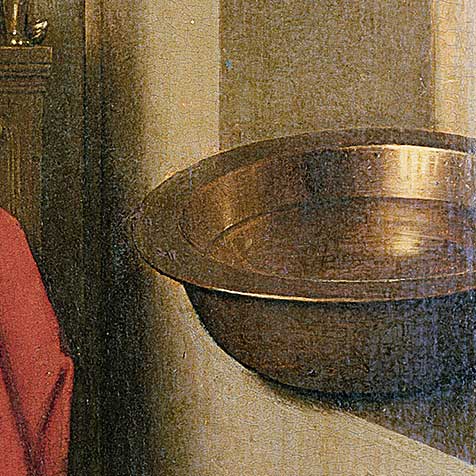

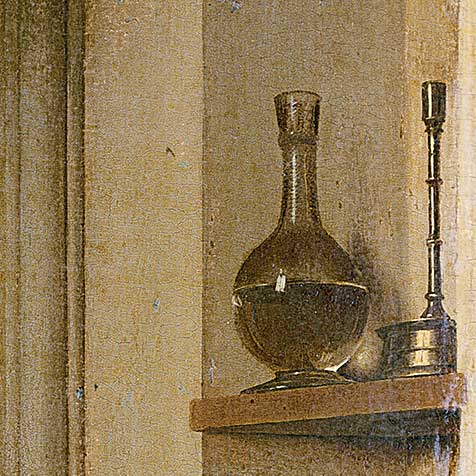

„ALS ICH CAN“AS WELL AS I CAN

Jan van Eyck – An eye for detail

THE ANNUNCIATION

Van Eyck was aware of his exceptional skill. With a combination of modesty and pride, he frequently accompanied the signature of his works with the motto “Als ich can” – “As well as I can”.

Johann David Passavant purchased the Lucca Madonna on behalf of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut at an auction in 1850. The Annunciation was sold to a different buyer following a fierce bidding contest at the same event.

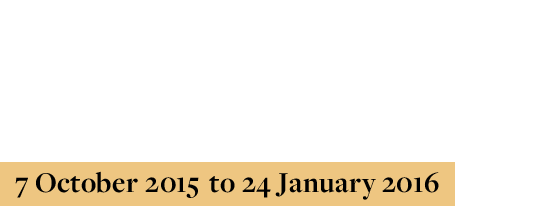

THE FEMININE IDEALSIMONETTA AND AURELIA

Sandro Botticelli meets Dante Gabriel Rossetti

THE QUEEN OF BEAUTY

The panel’s size, unusually large for portraits of women in the artist’s day, can be cited in support of the ideal portrait theory. Rather than being shown in straight profile, the lady turns slightly towards the viewer. Her elaborate braided coiffure, embellished with ribbons, pearls and feathers, corresponds to contemporary feast day fashions. Her porcelain-like complexion, high forehead, partially lowered lids beneath gently curving brows, and sensuous lips – these facial features are encountered in several paintings by Botticelli. What is more, his female figures always radiate a sense of dreamy melancholy.

It is possible that the lady with the captivatingly mournful gaze was Simonetta Vespucci (ca. 1453–ca. 1476).The young woman of Genoa had married into the aristocratic Vespucci family of Florence, and evidently bewitched the entire town with her beauty. Giuliano Medici, one of the most powerful Florentines of his time, had chosen her as his tournament lady and “queen of beauty”. After her premature death in April 1476 she took on the status of a mythical cult figure.

I look at the amorous beautiful mouth,

The spacious forehead which her locks enclose,

The small white teeth, the straight and shapely nose,

And the clear brows of a sweet pencilling.

Fazio degli Uberti, translation by Dante Gabriel Rossetti 2

THE BEAUTIFUL BELOVED

An interval of four hundred years separates the two works. Comparison of the pictorial theme and composition strongly suggests that Rossetti studied Botticelli’s ideal portraits closely. The juxtaposition once again sparks debate on the depiction of ideal beauty.

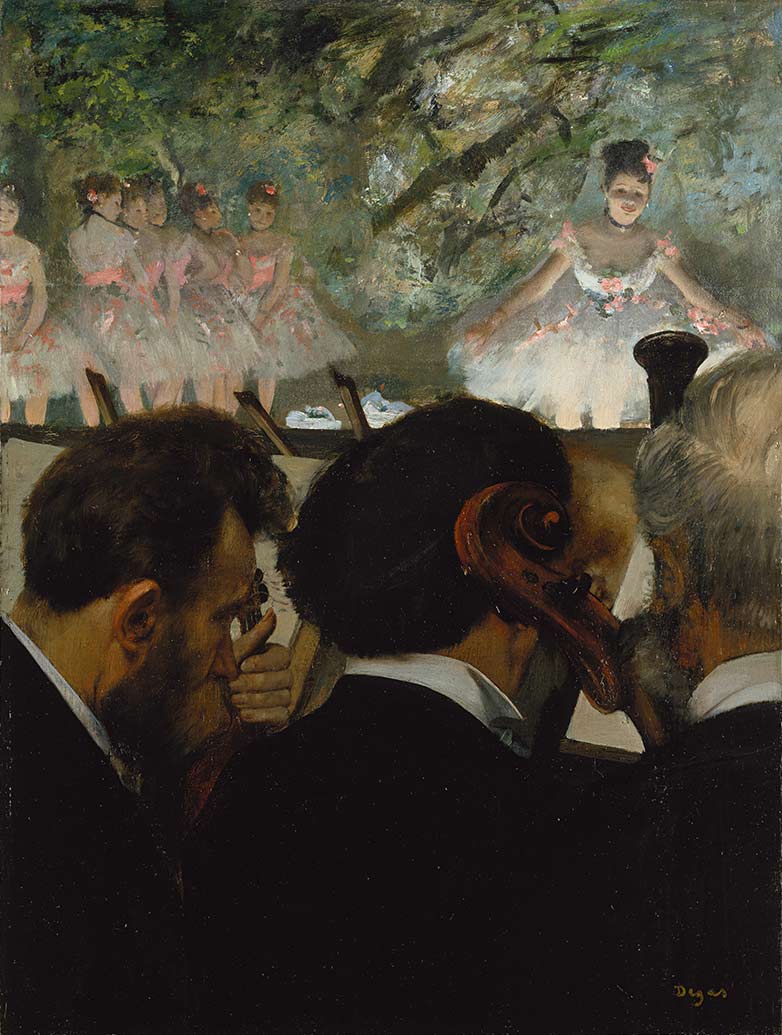

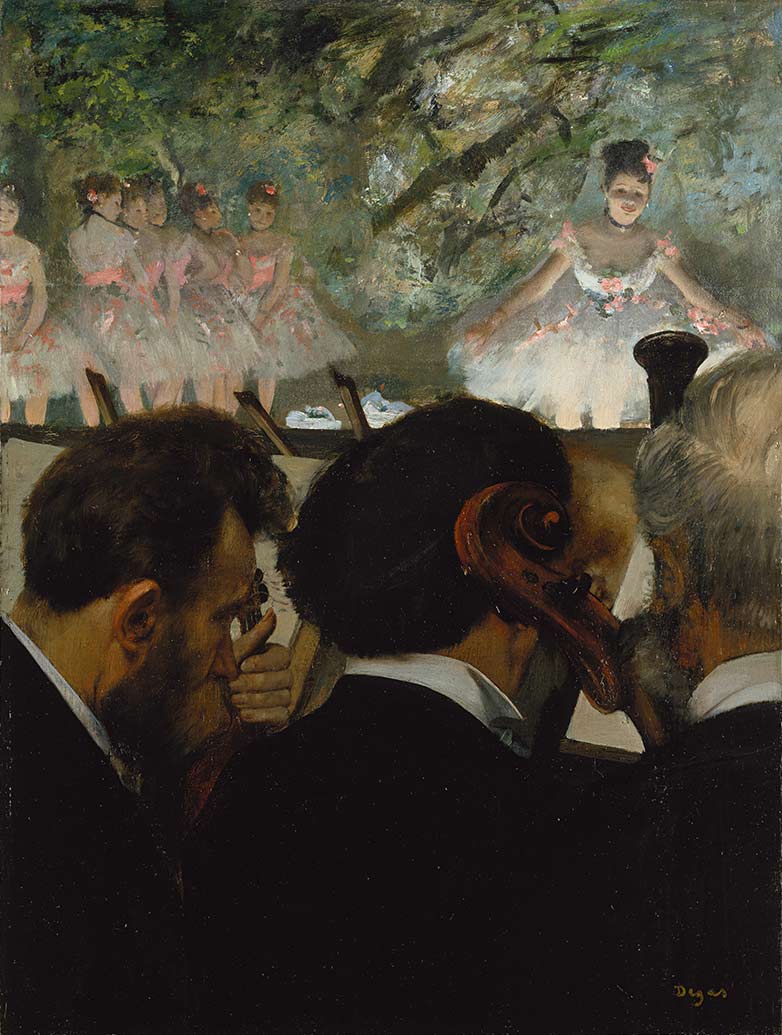

LIGHT-FOOTED BALLERINAS

Edgar Degas

FRIENDS OF MUSIC

THE NUNS’ DANCE

This Ballet Scene is one of Degas’s most condensed and sophisticated compositions. It was inspired by Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Robert the Devil. For his depiction the artist chose the most famous scene: two dead nuns awaken to new life in the ruins of a convent. With their frightening and wildly exotic dance they attempt to cast a spell over Robert.

The drama of the goings-on is underscored by the extreme spatial depth. The dancers, depicted hazily with broad brushstrokes, possess a ghostly quality. In marked contrast, the opera-goers in the foreground have been described with clear contours.

JUDITH AND DELILAHTWO STRONG WOMEN

Rembrandt meets Artemisia Gentileschi

SAMSON AND DELILAH – A HORRIBLE BETRAYAL

The scene of Samson’s blinding has rarely been depicted in as brutal and realistic a manner. The story continues, however. Following the horrible betrayal, Samson’s hair grows back. With his newly regained strength he takes revenge on his adversaries. In Rembrandt’s (1606–1669) day, Samson – a lone fighter against a superior enemy – was an important identification figure for the ruling classes in Holland.

In 1607, during the Eighty Years’ War, the Spanish armada had launched a surprise attack on the Netherlands. The Spanish, however, were overwhelmingly defeated and lost their supremacy at sea.

JUDITH AND HOLOFERNES – A VICIOUS MURDER

Holofernes lay on his bed, fast asleep, being exceedingly drunk. … Judith … went to the pillar that was at his bed’s head, and loosed his sword … took him by the hair of his head and said: Strengthen me, O Lord God, at this hour. And she … cut off his head … And after a while she went out, and delivered the head of Holofernes to her maid, and bad her put it into her wallet.

From the apocryphal Book of Judith 3

The painting is the work of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–ca. 1653). It was only because she had access to her father’s workshop that Artemisia succeeded in completing her training as an artist. She was to return to the theme of beheading and self-administered justice again and again.

The artist was herself a victim of violent sexual attacks inflicted on her by one of her father’s artist colleagues. The society of her time sought the guilt in the woman as a matter of course.

Against massive resistance, Artemisia defended herself by successfully taking her violator to court.

The close proximity of the protagonists to the viewer lends the scene heightened intensity. The painting differs from other depictions of the story in that here the maidservant takes active part in the killing. She presses Holofernes’ body down with all her strength. This scene will surely have made a deep impression on Rembrandt. It is not known whether he was acquainted with it from a drawing or an engraved copy.

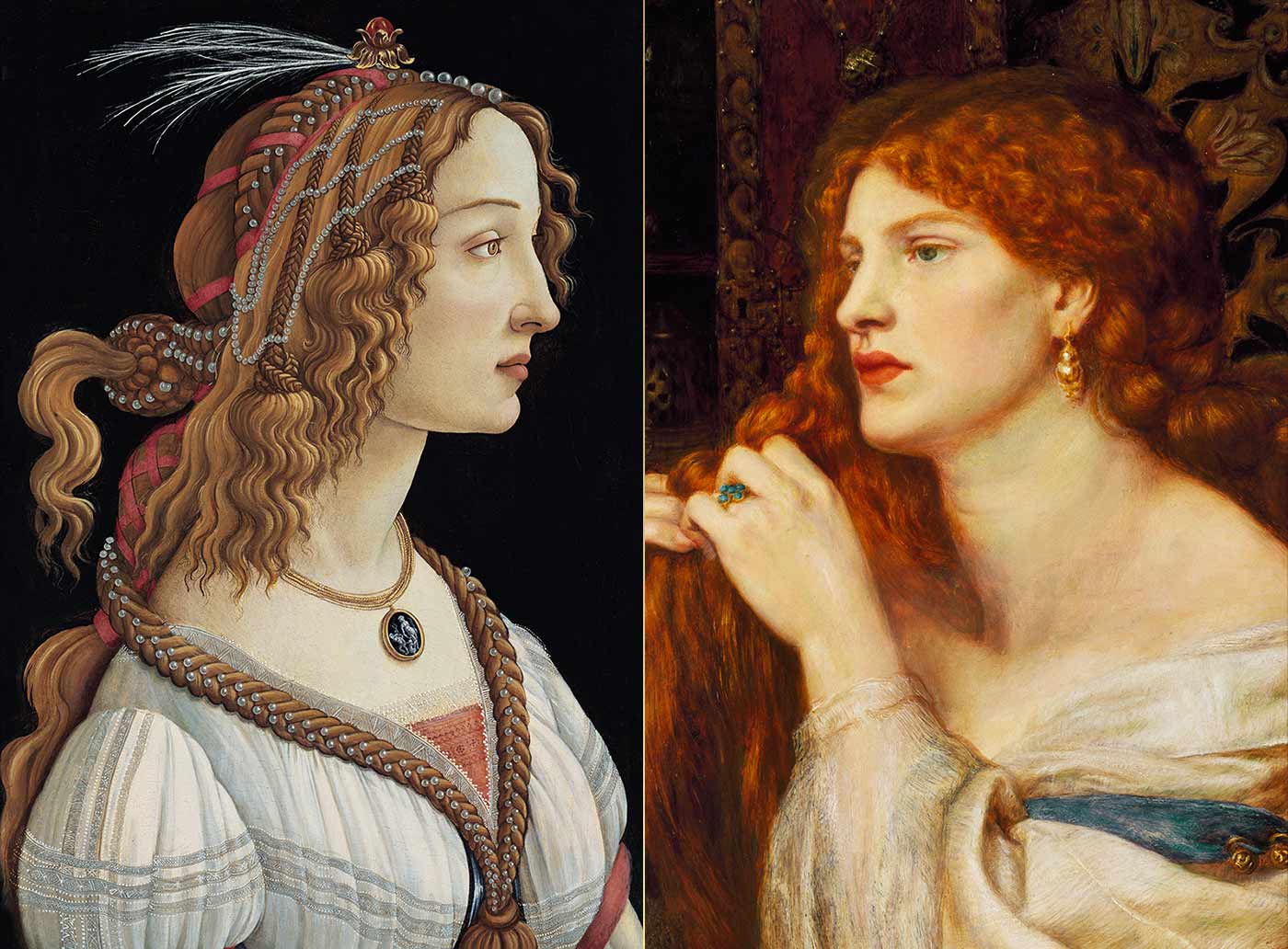

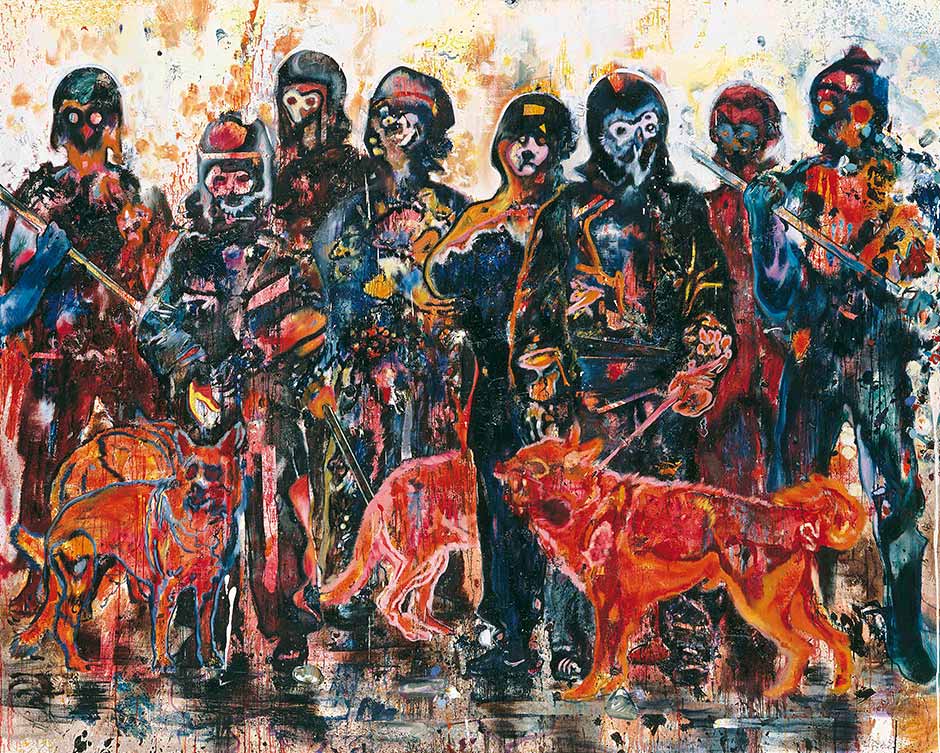

COLLECTIVEFEAR

Daniel Richter’s „Gaggle“

SINISTER CHARACTERS

In his paintings, the German artist Daniel Richter (*1962) explores photography as a means of reproducing reality. He is interested in images of present-day events from television, internet and the print media. Protests, disasters, street riots, civil wars – in the paintings in his work series, Richter creates a mood of collective fear and violence. Dog Planet and Gaggle have their pictorial theme and a certain painterly ambiguity in common. They differ in their respective experimental treatment of the colours and abstract surfaces, and the manner in which they play with contrasts.

AS IF CHISELLEDFROM STONE

Picasso and Fernande

Fernande’s face breaks up into rectangular and rhombic shapes. Picasso shows it from a number of different angles simultaneously. The chin and nose, for example, are seen from below and from the front. The portrait served as the formal point of departure for Picasso’s first Cubist sculpture. He translated the two-dimensional painting into a three dimensionally modelled shape with surprising directness. The result is an intense dialogue between painting and sculpture.

Cubism is … an art which is primarily concerned with form, and, once a form has been created, then it exists and goes on living its own life.

Pablo Picasso, 1923 4

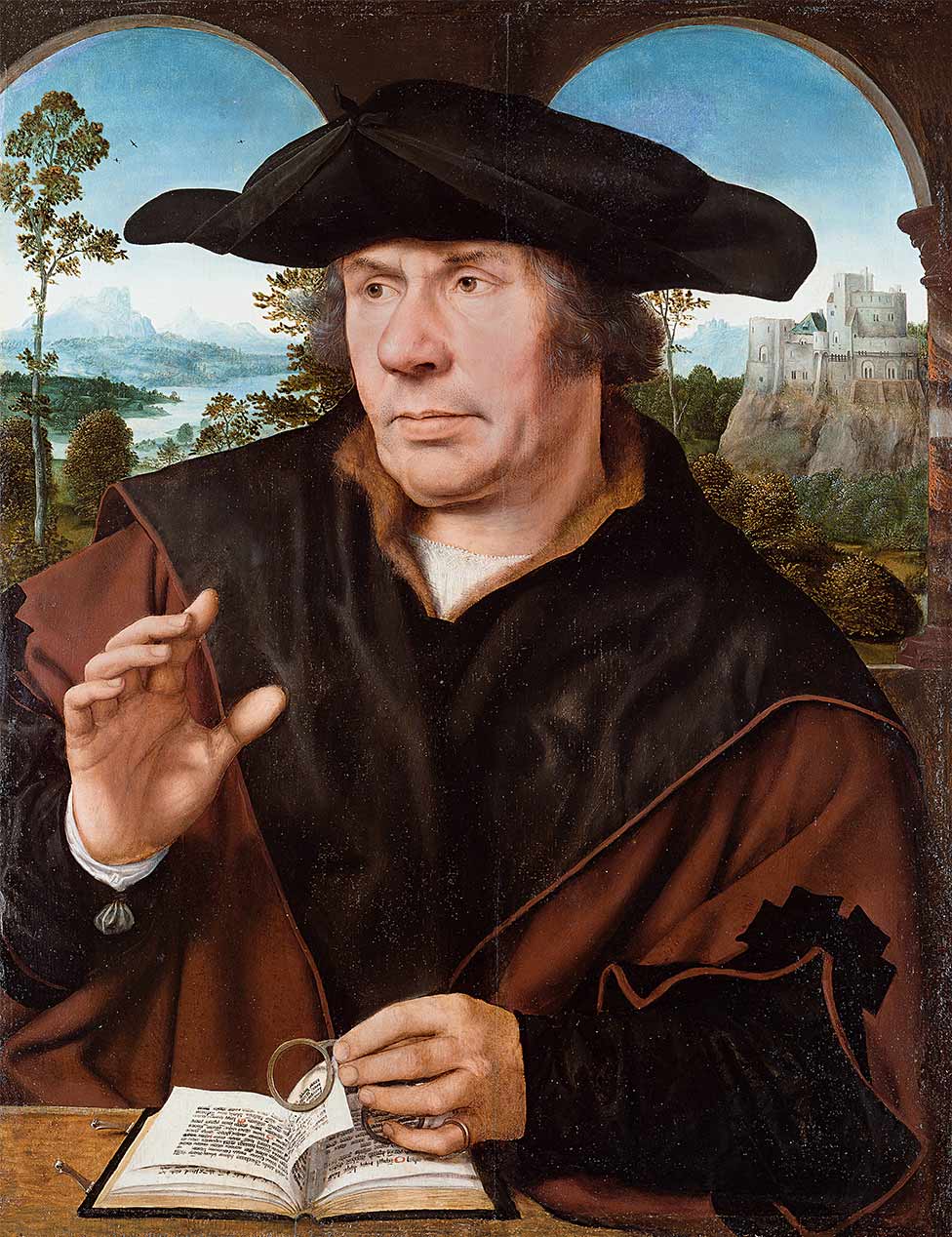

THE MASTERDRAUGHTSMAN

Hendrick Goltzius’s portraits

GILLIS VAN BREEN

At the bottom edge of the drawing is the inscription “…llis van Breen”. The name also turns up in another portrait of the same man. Gillis van Breen is thought to have been an engraver or printer of Haarlem. Goltzius executed several likenesses of him – the two men were evidently good friends. The drawing was not intended as a preliminary study, but as a work of art in its own right. This is clear from the fact that Goltzius signed the portrait.

FRIENDSHIP PORTRAITS

In the Portrait of Giambologna he created the likeness of the court sculptor to the famous Florentine family of bankers, the Medici. As was generally the case in his later portraits, he omitted the conspicuous signature. With the sparing use of red and black chalk, the artist achieved an amazingly painterly effect. He depicted the upper body as a loose contour drawing in black chalk that serves to bring out the rendering of the head in colour all the more strongly. Within just a few years, Goltzius had made great progress in the mastery of this complex drawing technique. The development is especially evident in the direct comparison of the two works.